At the Center for Historic and Military Archaeology, Heidelberg University

Although working in the field is a major component of archaeology, lab work comprises the majority of an archaeologist’s time. The lab is where everything comes together, be it analysis, background research, or actual artifact refitting. There are a multitude of tasks done in the lab, but our main focus as field school students is artifact processing and refitting. Artifact processing involves multiple steps, beginning with the removal and sorting of cultural materials before they are washed, sorted more specifically, and then refitting of glassware and ceramics. The processing procedure is a long and tedious one that requires patience and attention to detail, but is a necessary and rewarding part of the job.

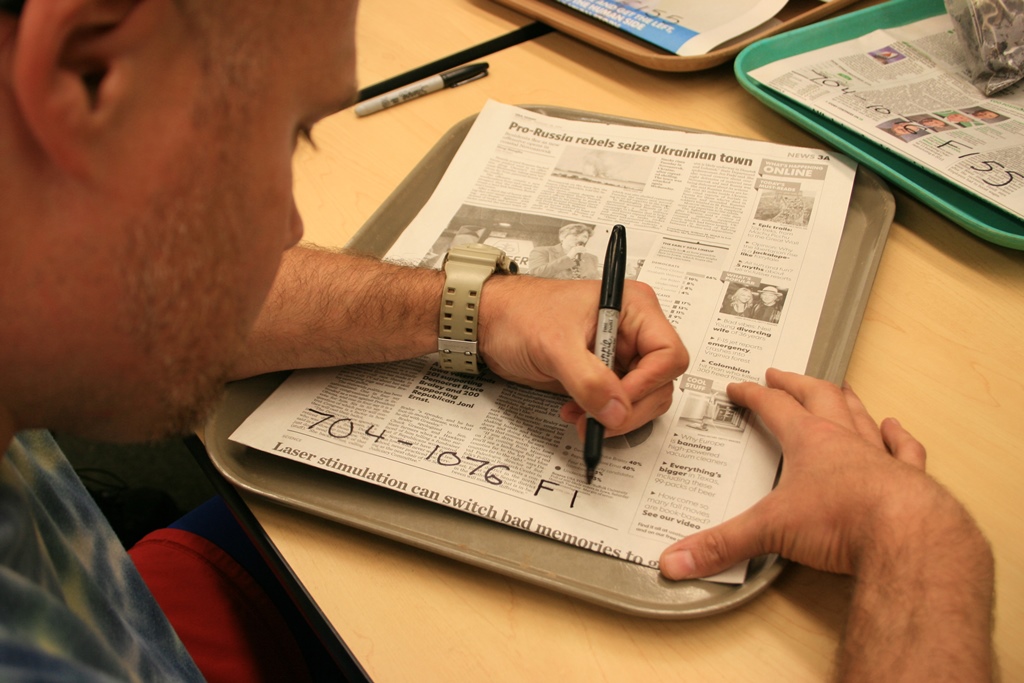

When we find cultural remains in the field, those that are not deemed a Field Specimen are kept together in a bag labeled with the assigned numbers of the unit or feature as well as 704 Number from the catalogue. The bags with the labeled provenience containing cultural remains are sorted together as one unit. We use lunch trays covered in newspaper labeled with the same 704 Number as the one on the bag. This is so there is no confusion during processing as to where the cultural material was recovered.

The items are then sorted by type. Some of the common types we find on Johnson’s Island are brick, nails, bone, window glass, ceramics, and glass bottle shards. They are all grouped together on the same tray, unless more trays are required due to a large amount of artifacts.

Once the artifacts are sorted we begin the process of cleaning. For a basic cleaning of these common artifacts, a soft bristled brush is used with clean water. By cleaning artifacts in this manner, we hope to remove as much of the surface dirt as possible and ensure that all edges are removed of any sort of particles that could keep the glue from sticking during the refitting process. Once washing is complete, the artifacts are left to dry.

When the artifacts are completely dry, we use archival pens to label the full 704 Number as stated earlier that is on the bag and then tray. Items like brick and nails are not labeled, but glass, bone and pottery and glass shards are commonly marked. Once labeled, we apply polyvinyl acetate over the number to protect it from being rubbed off. This way future workers in the lab will be able to identify the artifacts and know where they came from at the site.

Once the pieces have been cleaned it is time for us to do another round of sorting. For this sorting we include the Field Specimens in our task. We take pieces of glassware and ceramics and look for similar color and thickness and separate them out into different trays. We then look for different areas of the glass bottles and ceramics. Glass bottlenecks and finishes have a different look compared to the base, and ceramic rim pieces are distinguishable from smaller sherds off the center. Any indicators such as seems, scratches, or colors, helps to refit the individual pieces back together. By performing this process we are recreating cultural material in their entirety.

The whole purpose of resorting and integrating our FS-ed artifacts in with the smaller, less identifiable ones is for refitting. This is rather like putting together a puzzle, only with missing pieces here and there: difficult at first, but rewarding at the end. When we refit artifacts into their larger whole, we like to start with either the base or rim as they are the easiest to add other pieces to. However, sometimes in the first round of refitting you do not have much of either the base or rim and must make do. In those cases, we place the pieces that fit together in their proper order on the tray and set them aside until more of the pieces are discovered.

In order to refit, we focus on not only the edges of each glass shard or ceramic sherd, but the designs, scratches, inclusions, etc. as well. Each of these characteristics acts as a clue to how the pieces fit together. Not to say it is easy to refit. Refitting is a long process, and relies on our fieldwork to be completed. If we are in the process of excavating a feature while we are refitting, there is a high probability that some of our missing pieces have yet to be uncovered. If one or more of the connecting artifacts has been FS-ed, we place the artifact bag along with the pieces together on a tray to keep track of which artifacts go where. What pieces we are able to glue together easily we do with polyvinyl acetate, the same adhesive we use to keep the labels from rubbing off the artifacts. However, there are different concentrations. For thinner pieces of glass we use a 10% solution, and for thicker shards as well as ceramics we tend to use a 30% solution as it is thicker and acts as a stronger binding agent. Once the pieces are refitted and glued together, they are set in sand to ensure they dry properly. And then the process repeats itself until we have refitted everything that we can.

Archaeology is a destructive process, particularly archaeological fieldwork. Working in the lab is a bit different though; it is not nearly as destructive. Refitting is especially satisfying because it allows us to quite literally reconstruct once broken objects in hopes of better understanding their appearance and use at Johnson’s Island. Lab work does take time—much longer than the fieldwork aspect of archaeology—but the purpose is to understand the lifeways of past humans after all, and no matter how much fun we have digging at the site, it is the artifacts we find and their processing and analysis in the lab that give us the answers we seek.

Do you get involved in conservation of some of the artifacts?

Also can you provide a copy (blank) of the sheets from the field and the ones used in the laboratory? Your forms may have some detail that are usfull.

Thanks

Jim Denison, Community Archaeology Program, Schenectady County Community College, Schenectady, NY

Just want to let you know how much I appreciate your work on this site. My great-great-great grandfather was a prisoner there and left a diary that includes accounts of life there. Keep up the good work!